When Mold Steals Your Sleep

When circadian hygiene is not enough: Mold and Sleep Disruption

Sleep is one of the most delicate pillars of health and one of the first systems to destabilize in modern life.

Insomnia has quietly become one of the most widespread global health concerns of our time, accelerating alongside individualized technology and prolonged indoor living.

In the United States alone, an estimated 50 to 70 million people are affected each year, with women experiencing chronic sleep disturbances at rates roughly 40 percent higher than men.

Sleep functions as an active restorative state that drives repair across multiple systems. During deep sleep, the body increases the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, both of which support neuroprotection and inflammation control. When sleep becomes fragmented or shallow, these repair pathways lose efficiency, increasing vulnerability to oxidative stress and nervous system inflammation.

Over the past decade, interest in sleep optimization has guided many people back toward nature-aligned practices that have become foundational strategies for supporting circadian alignment:

reducing blue light exposure

limiting non-native electromagnetic field exposure

spending time outdoors

grounding

reconnecting with sunrise and sunset rhythms

In some cases, sleep remains disrupted even when these practices are consistently applied.

Understanding why requires a closer look at circadian biology.

Circadian rhythms developed in response to the Earth’s light and dark cycle. Nearly all living organisms rely on internal timing systems that anticipate and adapt to daily environmental changes. In mammals, the central circadian clock is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus. This structure receives light input through the eyes and synchronizes peripheral clocks across tissues and organs.

Recent research suggests that circadian rhythm regulation extends beyond human cells. Certain microorganisms within the gut exhibit rhythmic oscillations that appear to coordinate with the host’s circadian system.

These microbial rhythms influence immune signalling, metabolism, and sleep patterns. Disruption within this ecosystem is commonly associated with systemic inflammation.

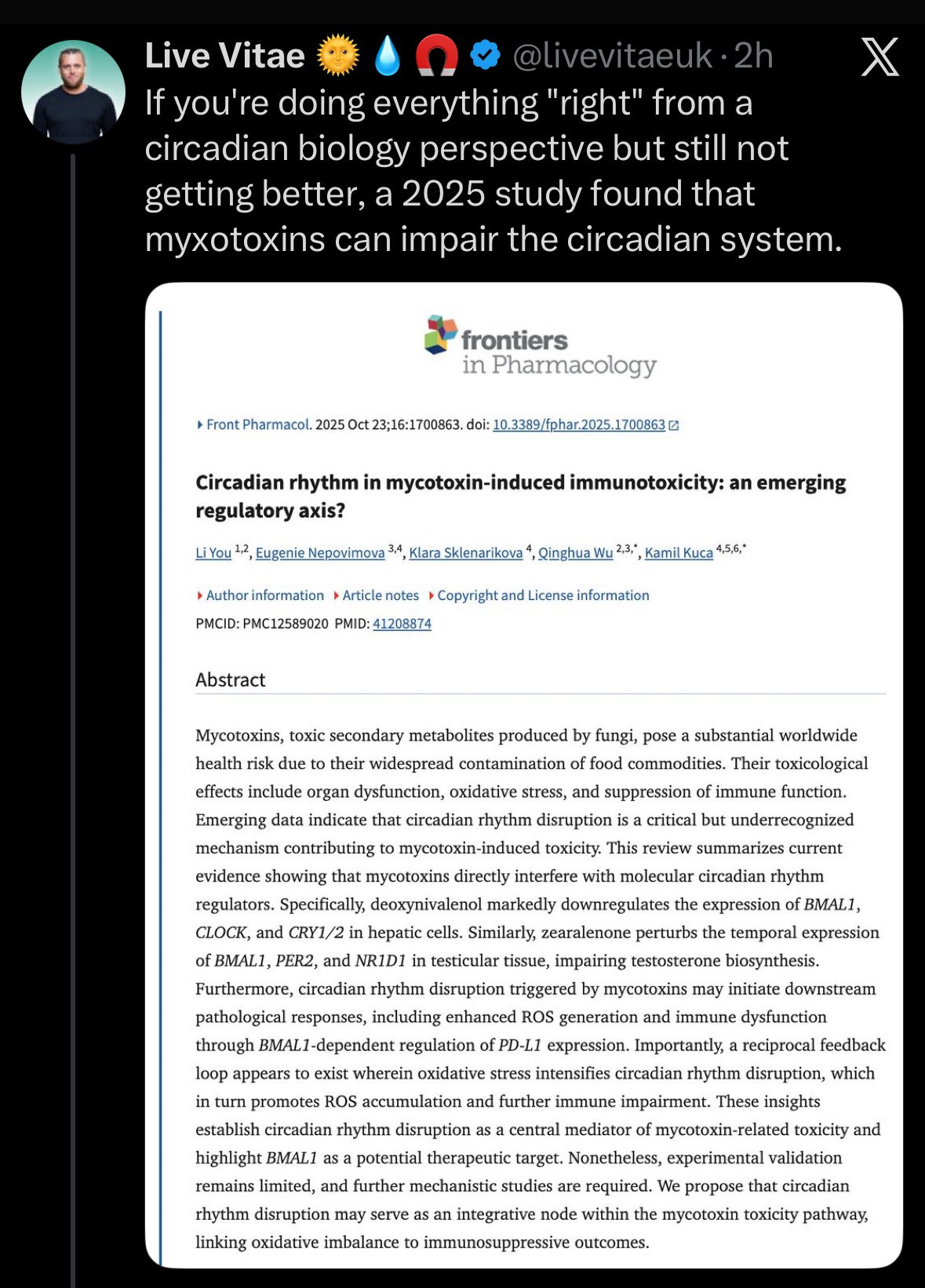

Bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections have all been shown to interfere with circadian signalling. Mold organisms and their secondary metabolites, known as mycotoxins, appear to have a particularly strong association with persistent and unexplained insomnia.

Mold exposure is more prevalent than commonly assumed. It develops in damp environments created by floods, roof leaks, condensation, construction defects, and water intrusion. Mold can be present in homes, offices, schools, vehicles, and ventilation systems.

Current estimates suggest that nearly half of residential buildings in the United States show signs of dampness. Approximately half of indoor mold growth remains hidden within walls, carpets, or HVAC systems. In an EPA investigation of commercial office buildings, 85 percent showed evidence of past water damage, and nearly half had ongoing leakage issues.